A new look at decades-old data from the Apollo missions has revealed evidence of tens of thousands of previously unknown lunar earthquakes. The results could reveal details about the inner workings of the moon and could have implications for future human missions.

“There were more tectonic events on the Moon, it is more tectonically active than previously thought,” says planetary seismologist Keisuke Onodera of the University of Tokyo. By meticulously examining seismic waveforms, Onodera found 22,000 previously unseen moonquakes, he reports July 5 in JGR: Planets.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Apollo missions that landed on the Moon carried two types of seismometers: one to measure the longer-period seismic waves that originated deeper underground, and one to measure the shorter-period waves that originated closer to the surface or it. carries more energy (SN: 15.7.19).

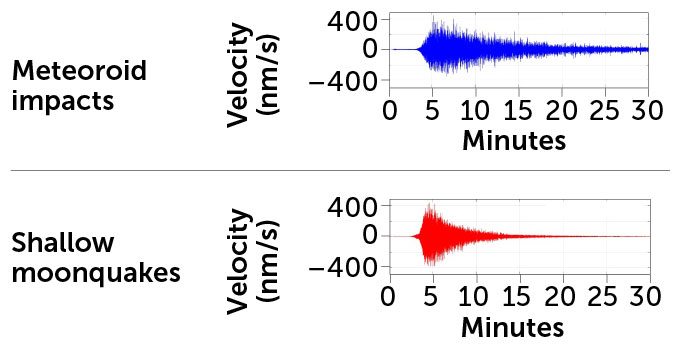

Seismometers plot the shape of the waves that shake the ground – some are low and damp quickly, while others are long and narrow. Based on the shapes, scientists can learn about the origin of the earthquake.

Some of these seismographs took data almost continuously from 1969 to 1977, recording about 13,000 seismic events (SN: 5/13/19). But most of the data from the short-period seismometers were so contaminated with other wave sources that they were almost unusable at the time.

“This is 50 years of data that people had to deal with mostly by hand,” says California-based lunar seismologist Ceri Nunn, who was not involved in the new study. “You’ll print them on an old dot matrix printer and draw them by hand.”

So lunar scientists knew they were probably missing some lunar earthquakes from that time period. But no one had actually sat down and sifted through the data to find out how many there were, until Onodera turned his attention to it last year.

“The most surprising thing is that I detected 22,000 – a much larger number of events than the original data set,” says Onodera. The new earthquakes bring the total number known to 35,000. “This is something no one expected.”

Onodera looked at the graph of each individual seismic event by eye and categorized them one by one based on their shape. Other lunar scientists were amazed by this low-tech precision.

“It’s natural intelligence, I would say, not artificial intelligence,” says planetary geophysicist Raphaël Garcia of ISAE-Supaero in Toulouse, France, who was not involved in the study. “I’m sure it’s a big deal. He reworked everything.”

Most of the newly identified earthquakes were from external sources such as extreme temperature changes or impacts, including cases where NASA deliberately dropped rocket boosters or lunar modules on the surface of the moon to see what they did. But some were shallow moonquakes that reflect movements originating in the upper few kilometers of the moon’s crust. These earthquakes are the ones most likely to provide information about the inner workings of the moon.

Previous studies had identified 28 shallow moonquakes during eight years of observations. Onodera found 46 more, significantly increasing the total number of shallow moonquakes.

He also found that these shallow wobbles appeared to be more common in the northern hemisphere, near the Apollo 15 landing site, than near the more southern sites of Apollo 14 and 16. Gravity data from NASA’s GRAIL probes, which crashed into the lunar surface in 2012, indicated that volcanic craters also surround the Apollo 15 site. (SN: 12/14/12). Shallow moonquakes can form when the moon’s crust contracts around these denser intrusions, Onodera suggests.

Getting a better handle on the frequency and strength of lunar earthquakes will be important in planning human trips to and structures on the Moon. Seismic data can help measure the depth of the lunar soil, which can determine how much construction material astronauts will have to work with. The measurements could also set limits on how much shaking lunar habitats should withstand and indicate where the safest landing sites might be.

Fortunately, lunar scientists should soon have a lot more data to work with. NASA and commercial partners are planning to send a pair of seismometers to the far side of the Moon in 2025. And China’s Chang’e 7 mission will send another seismometer to the lunar south pole in 2026.

“It’s kind of a golden age for planetary seismology,” says Garcia, who is one of the principal investigators for the 2025 mission.

#Moonquakes #common #previously #thought #Apollo #data #suggest

Image Source : www.sciencenews.org